In the first part of this post I discussed the intervals from unison to the perfect 5th, and references to identify them with. Check it out if you haven’t already! Let’s take a look at the next set of intervals.

Don’t forget, all of my MIDI piano examples start on a C. The song examples I give may not necessary be starting on a C, so don’t let that throw you off. Hopefully this will help you learn to identify them no matter what the starting notes are. It’s the space between the notes that you care about, not the notes themselves!

Minor 6th

Separate:

Together:

The minor 6th, to me, is a sort of dreamy sounding interval. Perhaps this is because one of the ways I like to remember it is through “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz. You can hear it in the lyrics:

Check it out:

(Audio taken from this video)

Keep this song in mind, as it’s going to show up two more times in this post!

Major 6th

Separate:

Together:

There are two references that I like to use for the major 6th. The NBC chimes are a perfect example:

(Audio taken from this video)

You can also listen to the line before the minor 6th in “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”.

Listen here:

(Audio taken from this video)

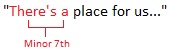

Minor 7th

Separate:

Together:

For the minor 7th we can once again refer to the West Side Story musical. This time from the song “Somewhere”.

You can hear the minor 7th in the beginning of the line:

Listen here:

(audio taken from this video)

Major 7th

Separate:

Together:

The major 7th is one of my favorite intervals. It almost has an inherently jazzy sound to me, mostly due to the fact that jazz chords and melodies utilize the interval quite a bit. It’s also similar to the tritone in that it’s ALMOST a perfect interval (it’s ALMOST an octave, as the tritone is ALMOST a perfect 5th), so it has that off sound but in a soothing sort of way. Take Norah Jones’ “Don’t Know Why” for example. You can hear the major 7th in the first two words:

Listen here:

Craving a more 80’s synthpop/rock example? Try “Take On Me” by A-Ha.

Check it:

Octave

Separate:

Together:

Finally we come to the final interval I’m covering for this mini-series, the octave. This one represents 12 semitones and is the 8th note in a standard scale (thus the prefix, “oct”). Scientifically, an interval of an octave is what you get when you double the frequency of a note. For example, the A note above middle C has a frequency of 440 Hz. The next A note (or the A one octave higher) has a frequency of 880 Hz. The A after that is 1760 Hz, and so on.

Let’s once again refer to “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, which begins with the iconic:

Listen here:

Now to make my fellow guitarists happy, a little Hendrix. The intro to “Purple Haze” has Jimi repeating two notes an octave apart. This example is special, though, because if you listen closely you can hear that the bass is playing a tritone instead of an octave underneath the guitar. Two intervals for one.

Listen up:

That’s right, Jimi Hendrix and Judy Garland in the same section.

So there you have it. A few examples for each interval from unison to octave. Again, I only covered the intervals going in the upward direction, so I may make a post for intervals going down later (let me know what you think). Obviously there are plenty more examples for each interval, but I did my best to stick with classic examples that more people are probably aware of.

A fantastic link that you should check out for interval ear training (and ear training in general) is www.musictheory.net. Specifically the interval ear trainer. By fiddling with the options you can set which intervals you want to practice, whether they are ascending or descending, and more. Test yourself and try to improve. If you get a score you’re proud of, brag about it in the comments.

Do you have your own examples for each interval? How do you like to memorize them? Let me know!

Next post in the series: Identifying Scales